"Hemodynamic Instability and Cardiovascular Disease after Spinal Cord Injury"

Date: 16 December 2025

Reading time: 3-5 mins

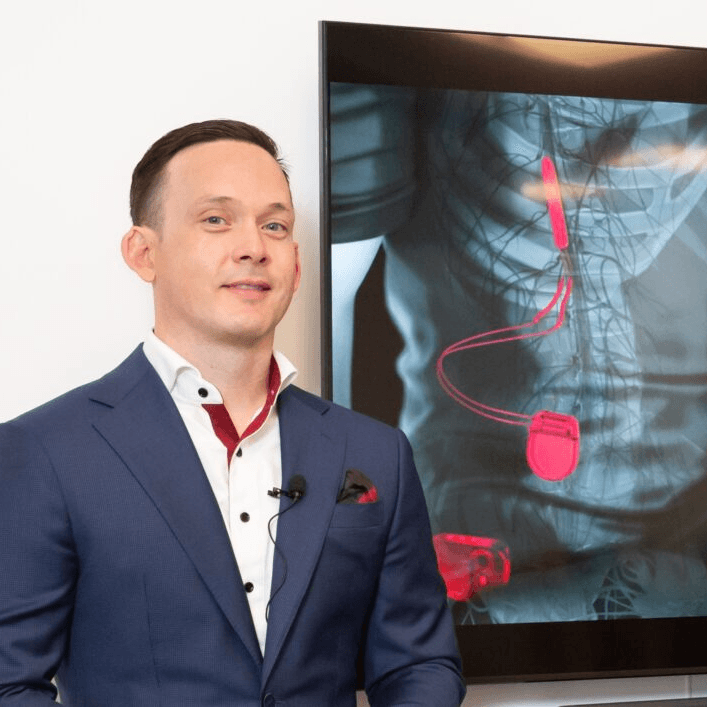

Author: Dr. Aaron Phillips, University of Calgary, Canada

Aaron A. Phillips, PhD, Associate Professor, University of Calgary, and a schematic of the implantable system based on biomimetic epidural electrical stimulation (EES) of the spinal cord.

Why Hemodynamic Monitoring Matters in Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)

Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death worldwide. Most people recognize the usual risks: poor fitness, excess weight, high blood pressure, smoking. What almost nobody realizes is that after a Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) the danger is not just slightly higher. It is dramatically higher. The best contemporary data show that a person living with Spinal Cord Injury is close to six times more likely to develop cardiovascular disease compared with someone without an injury of the same age (1).

To put that in perspective, a six-fold increase in risk places Spinal Cord Injury in the same league as some of the most well-established and alarming risk states in medicine.

It is comparable to the risk of cirrhosis in someone who drinks heavily for years (2,3).

It rivals the likelihood of progressing to type two diabetes in a person with class two or class three obesity (4,5).

It mirrors the risk carried by people with a strong family history of early heart attack (6).

The astonishing part is that most clinicians and patients never hear these comparisons. Yet the data are consistent: cardiovascular disease is not a distant complication after Spinal Cord Injury. It is a central and aggressive threat.

In this blog post, you can find out how SCI alters cardiovascular regulation and why better detection and earlier intervention, lead to better long-term independence, participation and survival.

The key discussion points are:

- How SCI reshapes cardiovascular physiology

- How cardiovascular risk should be assessed after SCI

- Why high-resolution hemodynamic monitoring matters

- Improving long-term health and quality of life

How Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Reshapes Cardiovascular Physiology

SCI alters many components of cardiovascular regulation. The severity depends on the neurological level and completeness of injury. Key mechanisms include loss of descending sympathetic control, baroreflex dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, autonomic dysreflexia and physical deconditioning. These factors combine to create a type of cardiovascular stress that differs sharply from the patterns seen in the general population (7).

Why standard cardiovascular risk tools underestimate danger

Most cardiovascular risk calculators assume intact autonomic pathways and stable hemodynamics. Those assumptions do not hold after SCI. Studies show that standard scores underestimate true cardiovascular risk in this population, with a likely factor because that they miss hemodynamic instability and unusual metabolic patterns that accelerate vascular disease (8,9).

How Cardiovascular Risk should be assessed after Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)

The following key focus points are discussed here:

- Blood pressure across postural change

- Continuous or near-continuous hemodynamic monitoring

- Consideration of neurological level and completeness

Effective assessment should capture the dynamic behaviour of the cardiovascular system. Several measurements become particularly important:

- Blood pressure across postural change

Orthostatic positions reveal the magnitude of orthostatic load and the adequacy of sympathetic compensation. Testing while seated, or using a

tilt-table testing provides a structured way to quantify this.

- Continuous or near-continuous hemodynamic monitoring

Ideally, cardiovascular function should be observed beat-to-beat because the most clinically important disturbances. Orthostatic hypotension, blood pressure lability, baroreflex failure and autonomic dysreflexia, often unfold within seconds. High-temporal-resolution monitoring captures instability that standard clinic readings cannot. While not always mandatory in routine care, it is a very informative approach for understanding autonomic and vascular health after SCI.

- Consideration of neurological level and completeness

Higher injuries and more complete lesions are consistently linked to greater autonomic impairment and higher cardiovascular risk.

Why High-resolution Hemodynamic Monitoring Matters

Hemodynamic instability is a defining feature of SCI, and it contributes directly to long-term cardiovascular disease. Tools capable of high temporal resolution offer several advantages:

- Detection of orthostatic hypotension even when transient.

- Characterization of baroreflex function.

- Identification of hypertensive episodes related to autonomic dysreflexia.

- Measurement of blood pressure variability during everyday activities.

- Evaluation of responses to spinal cord stimulation, rehabilitation, and standing training.

Although other measurement strategies can be useful, high-resolution monitoring provides the clearest window into autonomic function and cardiovascular stress in this population.

Improving Long-term Health and Quality of Life

Cardiovascular disease after SCI is not inevitable. Recognition and targeted management can likely slow or prevent progression. This likely includes treating hemodynamic instability, reducing triggers for autonomic dysreflexia, monitoring hemodynamics during rehabilitation and using interventions where needed. Our team has been focused on developing therapies for these conditions after SCI (10,11,12).

Better detection leads to earlier intervention. Earlier intervention leads to better long-term independence, participation and survival.

Want to know more?

Would you like to keep updated on Finapres®? Follow us on LinkedIn, X and BlueSky.

Do you want to read more about Finapres® devices? Read our brochures GAT and NOVA.

References

- Yoo, J. E. et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation after spinal cord injury. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, (2024).

- Nash, M. & Bilzon, J. Guideline approaches for cardioendocrine disease surveillance and treatment following spinal cord injury. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 6, (2018).

- Bellentani, S. et al. Drinking habits as cofactors of risk for alcohol-induced liver damage. Gut 41, 845–850 (1997).

doi:10.1136/gut.41.6.845 - Padmakumar, R. et al. Efficacy of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on type 2 diabetes with BMI less than 35: a retrospective study. J. Diabetes Obes. 2, (2015).

- Eyre, S., Bouatia-Naji, N., Vatin, V. et al. ENPP1 K121Q polymorphism and obesity, hyperglycaemia and type 2 diabetes in the prospective DESIR Study. Diabetologia 50, (2007).

- Ranthe, M. F. et al. A detailed family history of myocardial infarction and risk of myocardial infarction: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One 10, e0125896 (2015).

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125896 - Phillips, A. A. & Krassioukov, A. V. Contemporary cardiovascular concerns after spinal cord injury: mechanisms, maladaptations, and management. J. Neurotrauma 32, 1927–1942 (2015).

doi:10.1089/neu.2015.3903 - Barton, E. et al. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors strongly underestimate the five-year occurrence of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in individuals with spinal cord injury. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 36, (2021).

- Bauman, W. A., Kahn, N. N., Grimm, D. R. et al. Risk factors for atherogenesis and cardiovascular autonomic function in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 37, (1999).

- Phillips, A. A. et al. An implantable system to restore hemodynamic stability after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 31, 2946–2957 (2025).

- Soriano, J. E. et al. A neuronal architecture underlying autonomic dysreflexia. Nature 646, 1167–1177 (2025).

- Squair, J. W. et al. Neuroprosthetic baroreflex controls haemodynamics after spinal cord injury. Nature 590, 308–314 (2021).